Some children don’t fit neatly into one box. If your child seems both Autistic and ADHD, this article explains what AuDHD can look like day to day, without labels, pressure, or assumptions.

TL;DR

If you’re short on time, here’s what this article explains about AuDHD in children:

- What AuDHD means in simple, parent‑friendly terms

- How Autistic and ADHD traits can both support and clash with each other

- Why things like routines can feel both essential and impossible

- What this mix can look like in everyday family life

- Gentle reassurance if your child feels “hard to read”

This article is for / not for

This article is for:

- Parents whose child shows traits of both Autism and ADHD

- Families who feel one explanation never quite fits

- Parents looking for understanding rather than fixes

This article is not for:

- Diagnosing a child

- Replacing professional assessment or support

- Telling you how your child should be

Medical note

This article is for understanding and reassurance only. It does not diagnose or offer medical advice. If you’re exploring assessment or support in the UK, the NHS or recognised charities can help guide next steps.

Making sense of a mixed picture

Many parents notice that their child seems to hold two opposite needs at once. They might crave structure but resist it. They might focus intensely on one thing, yet struggle to stay with anything for long.

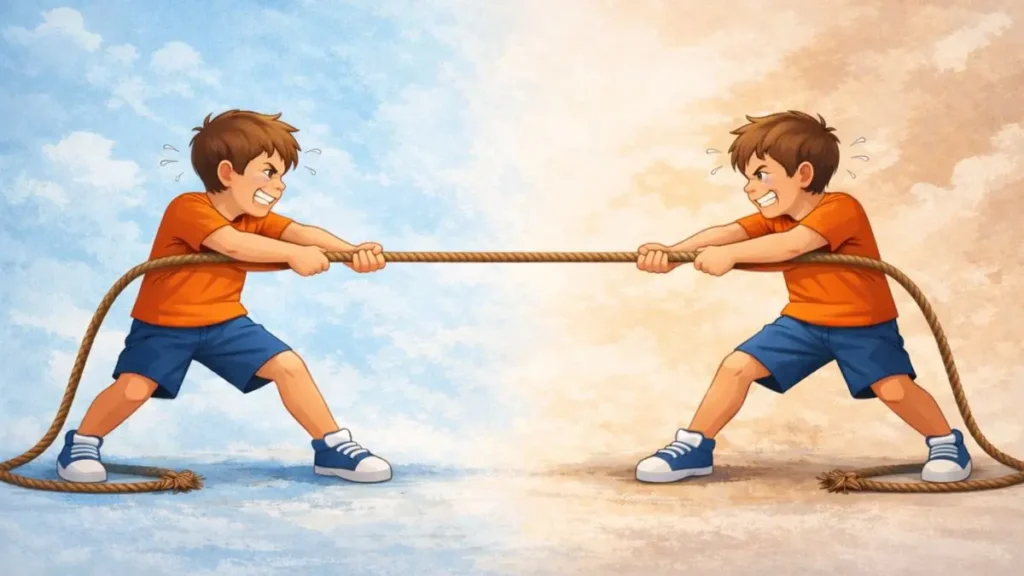

When a child is both autistic and ADHD, often called AuDHD, this push‑and‑pull can explain why things feel confusing, inconsistent, or harder to predict.

What AuDHD actually means

AuDHD isn’t a diagnosis on its own. It’s a shorthand parents and professionals sometimes use when a child meets the criteria for both Autism and ADHD.

It’s also worth knowing that this understanding is relatively recent. For a long time, Autism and ADHD were seen as separate, and it was often assumed a child could only be one or the other. Only in more recent years has it been widely recognised that the two can and do co‑exist in the same child.

Rather than cancelling each other out, these traits exist together, shaping how a child experiences the world, learns, plays, and copes with everyday demands.

When traits support each other

When Autism and ADHD come together, it isn’t always a struggle. In the right conditions, the two can balance each other in ways that bring real strengths to the surface.

Parents often notice that when their child is interested, supported, and not under pressure, these combined traits can lead to deep engagement, original thinking, and a strong emotional connection.

Some examples parents commonly recognise include:

- Deep interests (Autism) paired with energy and creativity (ADHD), which can lead to passionate learning or long periods of absorbed play

- Strong pattern‑spotting (Autism) alongside fast thinking (ADHD), which can support problem‑solving in unexpected ways

- Honesty and directness (Autism) mixed with emotional expressiveness (ADHD), which can result in very open, heartfelt communication

These strengths tend to show up most clearly when a child feels safe, understood, and free from constant correction.

When traits clash and make things harder

At other times, the same mix can feel exhausting, both for the child and for the adults around them. This is often where parents feel most confused or stuck.

That’s because the needs linked to Autism and ADHD don’t always line up. A child may genuinely need two opposite things at the same time.

A very common example is structure.

- Need for routines and predictability (Autism) paired with difficulty remembering, starting, or sticking to routines (ADHD), which can leave a child asking for structure but struggling to follow it

This can look like a child asking for rules, plans, or clear expectations, and then finding it almost impossible to follow through on them, even when they want to.

Parents may also notice other tensions, such as:

- Need for calm and low sensory input (Autism) alongside a drive for movement and stimulation (ADHD), leading to restlessness in quiet spaces

- Preference for familiarity and sameness (Autism) mixed with a pull towards novelty and new experiences (ADHD), which can make choices and transitions harder

- Sensitivity to change (Autism) combined with a quick loss of interest or boredom (ADHD), creating a constant sense of being unsettled

This isn’t defiance, laziness, or inconsistency. It’s a nervous system trying to meet competing needs at the same time.

What this can look like at home or school

Because these traits can pull in different directions, AuDHD can look very different from one day to the next. This is often why parents feel that others don’t quite “see” their child.

In everyday life, parents often describe things like:

- Big emotions that arrive quickly and pass just as fast

- Periods of intense focus followed by sudden disengagement

- Sensory sensitivities alongside sensory‑seeking behaviour

- Teachers or relatives seeing “two different children”, depending on the setting

This unpredictability is often what makes AuDHD hardest to recognise, and hardest to explain to schools, family members, or professionals.

A personal insight that may help

One thing that became clearer to me over time is that many of the hardest moments weren’t about understanding or effort. They were about capacity.

A child can know what helps them, want structure, and genuinely try, but still not be able to access those skills in that moment, or articulate what they want or need. Seeing it that way changed how I responded. It helped me move away from asking why won’t they? and towards asking what’s getting in the way right now?

That shift didn’t fix everything, but it did bring more patience, more flexibility, and far less self‑blame, for me and for my child.

Some reassurance and next steps

If your child feels hard to read, contradictory, or “out of step”, you’re not imagining it, and you’re not failing them.

Understanding the overlap can help you slow things down and respond differently.

Rather than trying to make everything consistent or “work properly”, it can support you to:

- Allow more time for your child, especially around transitions, which often reduces stress for everyone

- Stay calmer yourself, because rushing and pressure tend to increase overwhelm

- Respond with curiosity instead of correction

- Explain your child’s needs more clearly to others

- Reduce pressure to make everything consistent

Support doesn’t start with labels. It starts with noticing patterns and meeting your child where they are.

You may also find these articles helpful:

- Understanding neurodivergence in children

- Autism traits that don’t look like stereotypes

- Signs of ADHD in children that parents often miss

For UK‑based guidance and support:

Key takeaways

If you’ve read this far, take a moment. Nothing here is about doing more or getting it right. These takeaways are simply here to help you hold the bigger picture with a bit more kindness, for your child and for yourself.

- AuDHD describes a child who is both autistic and ADHD

- Traits can support each other and conflict

- Wanting structure but struggling to follow it is common

- Inconsistency often reflects competing needs, not behaviour problems

- Understanding the overlap can ease pressure for everyone